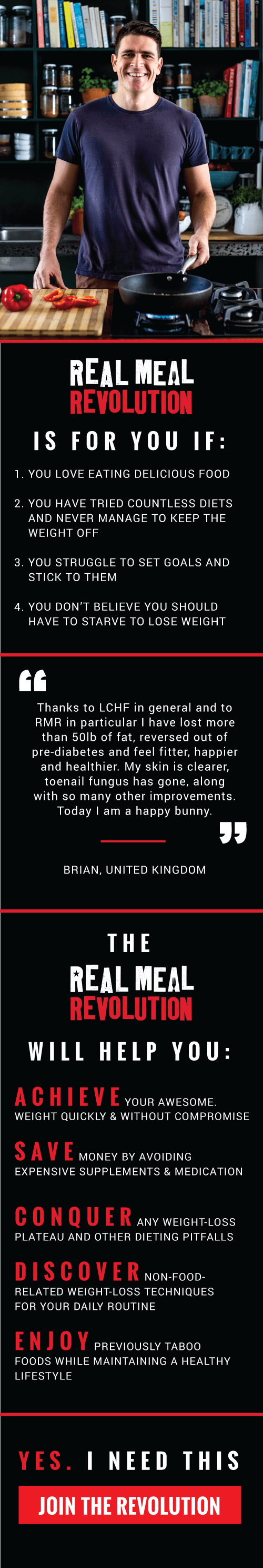

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now being recognised as one of the most common liver diseases, with more than 30% of adults in developed countries being diagnosed (1). As the name suggests it is a condition in people who don’t excessively drink alcohol which is marked by a large number of fat cells taking over the healthy liver tissue, causing fatigue and pain in those affected.

It’s not a disease which exists on its own. Instead, it is part of a group of diseases associated with metabolic dysfunction including metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes where the fat distribution and function is abnormal. As a result of these links, those with type 2 diabetes and obesity have nearly an 80% increased risk of NAFLD (1).

So what happens?

The liver is an important organ in the creation of energy from nutrients. It is closely linked to the gut by the portal vein, which shunts nutrients directly from the intestines, where they are absorbed into the bloodstream, to the liver for processing.

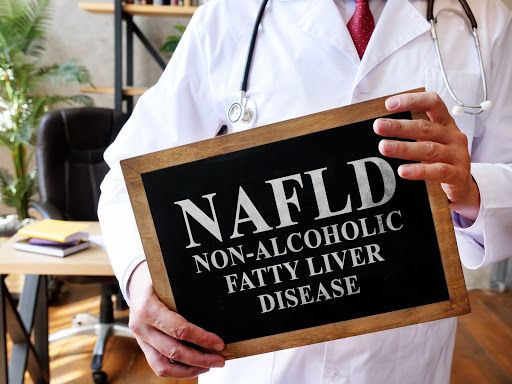

When we eat sugar it gets broken down into glucose and moved into the bloodstream. When this happens, the pancreas secretes insulin which transports the glucose into storage as glycogen in the muscles and fat in the fat cells. Then between meals and when we fast overnight, insulin goes down and our bodies tap into their store of energy, which happens so we don’t have to eat all day, every day. Like most of our organs and muscles, the liver can only store a small amount of glycogen and then it must be converted into fat for longer term storage.

Here’s where it links with type 2 diabetes and obesity. High insulin in response to a large amount of carbs (glucose) continues to push glucose into the available muscle cells and fat cells, filling them up and in the case of fat cells, creating more. High insulin also prevents us from burning the already stored fat (it doesn’t want us to tap into our reserves unless we absolutely have to).

So, if sugar continues to flood the system, the body continues to store it for later, pushing the newly made fat cells into all available spaces like a hoarder on a reality tv show (1,2).

The result is fat gets squished in around our organs as visceral fat, and between our skin and our muscles as subcutaneous fat – fat mess. As this continues over time, the system gets swamped and the incoming boxes of fat can’t be shipped out to storage quick enough to clear any room in the liver and eventually the liver is forced to hold on to them. It’s at this point in ‘Hoarders’ where a loving friend or relative calls in the network to help clear some space.

This is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and like hoarding, if left unchecked it has major consequences on our bodies, including cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation, and at the worst case, death (2).

Here’s where things get a little Joseph-Heller-like, the high insulin levels that are furiously trying to reduce the circulating glucose and increase fat storage to conserve the nutrients while simultaneously stopping the fat stores from being used, creates further problems with insulin resistance, which further perpetuates the high insulin levels, which further perpetuates the fat storage in organs and the insulin resistance which further perpetuates… well I think you get the point.

In other words, you store glucose as fat in the liver and the fat cells if you can’t store it in your muscles. And if you are insulin resistant, you keep storing more and more in your liver. Eventually your liver gets fatty. That is how a goose gets a fat liver too (from not responding well to a high carb, pure corn diet).

If you are insulin resistant and you eat tons of carbs, you can turn your liver into foie gras.

All is not lost!

Given the links with metabolic dysfunction, insulin resistance and high insulin levels, lifestyle change has been deemed as the most effective method for treating NAFLD (3). This includes cutting sugar and simple carbs like fructose as they are metabolised in the liver (4) as well as weight loss, to reduce the amount of visceral fat and reduce the risk of diabetes, heart disease and high blood lipids (dyslipidemia) (1).

This is where once again a Banting diet (Keto) saves the day, ticking all the boxes and addressing all the causes, reducing the burden on the liver to metabolise sugars as well as reducing insulin resistance, high insulin levels, visceral fat and obesity (5), allowing your body to ‘Marie Kondo’ the fat cells and remove the fat deposits within the organs.

In other words, if you cut carbs, you can turn your foie gras back into a liver.

Boom. Take that Foie Gras

- Dietrich, P and Hellerbrand, C. 2014, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, Volume 28, Issue 4, Pages 637-653, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.008.

- Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease – A global public health perspective. J Hepatol. 2019 Mar;70(3):531-544. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033. Epub 2018 Nov 9. PMID: 30414863.

- Blazina, I., Selph, S. Diabetes drugs for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Syst Rev 8, 295 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1200-8

- Schwarz JM, Noworolski SM, Erkin-Cakmak A, Korn NJ, Wen MJ, Tai VW, Jones GM, Palii SP, Velasco-Alin M, Pan K, Patterson BW, Gugliucci A, Lustig RH, Mulligan K. Effects of Dietary Fructose Restriction on Liver Fat, De Novo Lipogenesis, and Insulin Kinetics in Children With Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep;153(3):743-752. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.043. Epub 2017 Jun 1. PMID: 28579536; PMCID: PMC5813289.

- Mardinoglu, Adil et al. An Integrated Understanding of the Rapid Metabolic Benefits of a Carbohydrate-Restricted Diet on Hepatic Steatosis in Humans, Cell Metabolism, Volume 27, Issue 3, 559 – 571.e5