One of the most common frustrations we hear from women is this: “I’m training consistently. I’m pushing hard. So why does my midsection still feel stuck?”

It’s a fair question. Regular training is strongly associated with improved metabolic health, better body composition, and long-term weight maintenance. Resistance training supports muscle mass, cardiovascular training increases energy expenditure, and high-intensity sessions can improve fitness markers.

But fat loss, particularly around the abdomen, is not determined by exercise effort alone.

This week on our social platforms, we spoke about intensity, recovery, and why constant high stress may interfere with progress. Here, we’ll look at the physiology behind that conversation.

Exercise Is a Stressor and That’s Not a Bad Thing

Exercise creates stress in the body. In response, the body adapts. Muscles repair and strengthen. Cardiovascular capacity improves. Metabolic efficiency changes. This adaptive response is the reason training works.

However, adaptation depends on recovery.

If training intensity is consistently high and recovery is insufficient, whether due to low energy intake, poor sleep, or ongoing psychological stress, the body may struggle to adapt optimally. In some cases, prolonged energy deficits are associated with a small reduction in resting energy expenditure, a phenomenon known as adaptive thermogenesis (Rosenbaum & Leibel, 2010; Müller et al., 2015). This is a normal biological response to sustained calorie restriction.

In simple terms, the body becomes slightly more efficient when energy is scarce.

That does not mean metabolism “shuts down.” It means the body adjusts.

The Role of Fuel Availability

Another pattern we often see, particularly among women, is combining high training intensity with very low food intake. The intention is understandable: increase output, reduce input.

But consistently under-fuelling training can affect performance, recovery, and appetite regulation. Adequate protein intake is especially important during fat loss, as it supports lean mass retention and satiety (Phillips & Van Loon, 2011; Leidy et al., 2015). Lean muscle mass plays a role in insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health.

When calorie intake remains low for extended periods, hunger hormones such as ghrelin may increase, and feelings of fatigue may become more pronounced (Sumithran et al., 2011). These responses are not signs of weakness. They are regulatory mechanisms.

Training harder in this state does not necessarily accelerate fat loss. In some cases, it may simply increase physiological stress.

Stress, Cortisol, and Fat Distribution

Cortisol is often blamed for “belly fat,” but the reality is more nuanced.

Cortisol rises in response to many forms of stress, including exercise, lack of sleep, and psychological strain. Acute elevations are normal and necessary. Chronic dysregulation, however, has been associated in some research with changes in appetite, insulin sensitivity, and fat distribution (Epel et al., 2000; Spiegel et al., 2004).

This does not mean that one intense workout leads to abdominal fat storage. Rather, a broader pattern of high stress combined with insufficient recovery may influence how the body regulates energy over time.

Spot reduction is not supported by evidence. Core exercises strengthen abdominal muscles, but they do not selectively remove fat from the midsection (Vispute et al., 2011). Fat distribution is influenced by genetics, sex hormones, insulin dynamics, and overall energy balance.

Why Effort Alone Isn’t Enough

When someone says, “I’m doing everything right,” what that can mean is that they are training hard and eating less.

But fat loss is not simply a function of effort. It is influenced by:

Total energy balance over time

Protein intake and muscle preservation

Sleep quality

Stress load

Hormonal fluctuations

Blood glucose regulation

If several of these factors are misaligned, progress may feel slow, even when training is consistent.

This was the central message in our recent post: intensity is not the problem. Constant intensity without adequate recovery may be.

Where a Ketogenic Framework May Help

A well-formulated ketogenic approach does not replace training. Rather, it may support the metabolic environment in which training occurs.

When structured properly, keto focuses on lowering carbohydrate intake while maintaining adequate protein and including sufficient dietary fat. For some individuals, particularly those with insulin resistance, research suggests that carbohydrate restriction may improve glycaemic control and support fat loss (Feinman et al., 2015; Hallberg et al., 2018).

Lower-carbohydrate diets have also been associated with improved satiety in some populations, which can make energy intake easier to regulate without extreme restriction (Gibson et al., 2015).

Importantly, keto is not synonymous with under-eating. In fact, preserving lean mass through adequate protein intake is a key component of any sustainable fat-loss approach.

When training is supported with sufficient fuel and recovery, the body is more likely to adapt predictably. And predictable adaptation is what ultimately drives long-term change.

The Broader Perspective

Training hard is not inherently counterproductive. Exercise remains one of the most powerful tools for improving metabolic health, preserving muscle, and supporting long-term weight maintenance.

However, when high training intensity is layered onto chronic under-fuelling, insufficient recovery, and ongoing stress, results may stall. Not because effort is lacking, but because physiology prioritises stability. The body adapts to the conditions it is given.

Sustainable fat loss is rarely driven by effort alone. It depends on adequate protein, consistent energy intake, sufficient recovery, sleep quality, and blood glucose regulation. When these variables are aligned, training can do what it is designed to do: stimulate adaptation.

The question is not whether you are working hard enough. It is whether your current approach allows your body to respond predictably over time.

Progress does not require punishment. It requires structure.

For some women, the missing piece isn’t more effort, it’s better alignment between training, recovery, and nutrition.

That may mean adjusting intensity. It may mean fuelling differently. And for some, it may involve using a structured ketogenic approach to create more stable energy and appetite regulation.

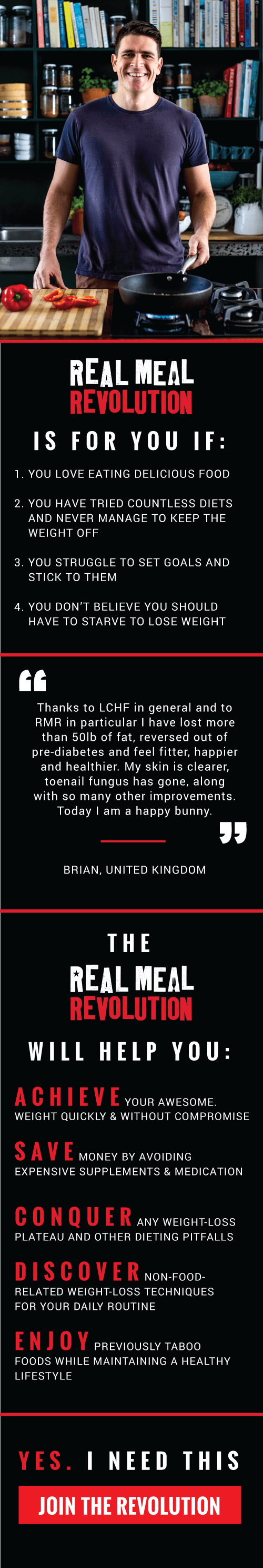

But structure matters.That’s why Real Meal Revolution works alongside Bridget Surtees, a registered keto dietitian to ensure keto is implemented properly, with adequate protein, appropriate fuel, and realistic expectations.

Because progress doesn’t come from pushing harder every time something stalls. It comes from building an approach your body can consistently respond to.